Participants from various fields, including media history, art history, musicology, history of science, sensorial ethnography, contemporary composition and sound art are invited to share experiences on how to perform historical re-enactments and how experimental research can serve or operate in artistic practice.

Questions to be addressed in the workshop include:

- What approaches, methods and techniques can we use in performing and disseminating historical re-enactments and hands-on experiments?

- What best practices and “artful failures” can we distinguish?

- How can we learn from other disciplines in performing and disseminating historical re-enactments and hands-on experiments?

- In what ways does the performance of historical experiments produce new forms of (tacit) knowledge?

- What are the performative qualities of experimental historiography?

- Can artistic practices that employ experimental historical research further the study of media archaeology? Is there a reciprocal relationship between the two?

By reflecting on these questions and sharing experiences and expertise as well as taking part in historical re-enactments and performances during the workshop, we aim to contribute to the development of a best practice guide on how to perform and disseminate media archaeological experiments in the DEMA research project.

Programme

Friday 18 December

10:00 Welcome and introduction to the DEMA project by Andreas Fickers and Stefan Krebs.

10:30 Panel I: Performative experiments in the DEMA project

Aleksander Kolkowski: Signal to noise

Signal to Noise is, in large part, an homage to Alvin Lucier’s seminal electro-acoustic composition “I am Sitting in a Room” (1969), where a narrator’s voice is recorded, played back into the room and re-recorded repeatedly until the natural acoustic resonances of the room are so reinforced that they overwhelm the speech. In this case, the room resonance is replaced with the noise produced by media format conversion and generation loss, achieved through the use of a hybrid tape and disc recorder; a Wilcox-Gay Recordio from ca 1951. The speech is recorded onto magnetic tape, transferred to a lacquer disc and back again to tape, all on the same machine. The cycle is repeated until the voice becomes subsumed and buried under layer upon layer of tape hiss and disc-cutting and surface noises. While this activity may be thought of as a creative reuse of historical audio technology, at the same time, it is a media-archaeological exploration into the usage and functions of the machine, highlighting its hybridity and also the noises inherent to the tape and disc media.

Tim van der Heijden: Performing a historical re-enactment: the making of a 16mm home movie

In this presentation, I will “perform” the making of a 16mm home movie based on my media archaeological experiments with an original Ciné-Kodak film camera from 1930. A split screen montage shows the recorded analogue film fragments besides footage that illustrates the process of making the film captured by my documentation equipment, including a digital video camera, GoPro and 360 degree camera. My contribution aims to discuss and re-evaluate the performative nature of media archaeological experiments, and how digital (documentation) tools enable new forms of presentation, explication and dissemination of historical tacit knowledge in early-twentieth century amateur filmmaking.

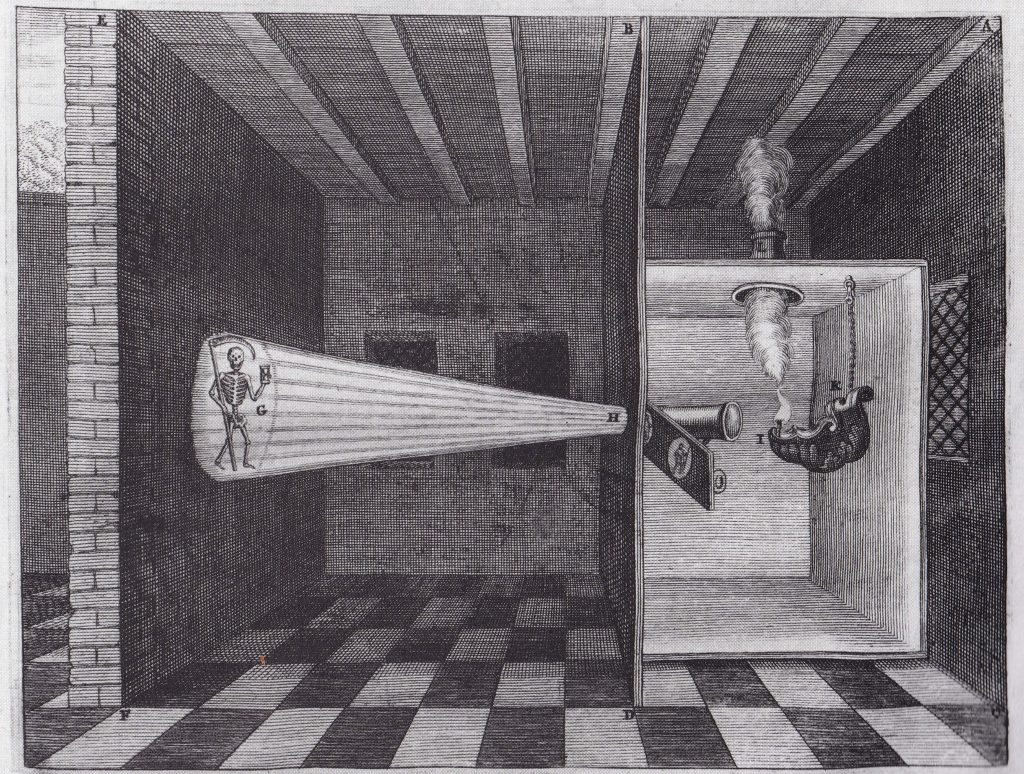

Ludwig Vogl-Bienek & Karin Bienek: Media-archaeological experiments with ‘Improved Phantasmagoria Lanterns’ (1820-1880)

The presentation gives a brief overview of a series of media archaeological experiments with “improved phantasmagoria lanterns”. This type of projection device was used from the 1820s to the 1870s to convey knowledge in an entertaining way. The experiments were conducted with surviving devices and associated glass slides (copperplate sliders). A screen for rear projection was used as a projection surface, which was reconstructed according to instructions from 1823. The presentation is illustrated with photographs and video sequences that were taken to document the experiments.

11:45 Break

12:00 Panel II: Performative experiments in sound and acoustics

Sean Williams: Bandpass filters in Stockhausen’s Sternklang

There’s an interesting conflict between mutually exclusive requirements of specific vowel sounds and specific harmonics required in Stockhausen’s Sternklang (1971), and I outline the technical challenges I had to deal with in order to realise this in a 2020 performance in Hannover, both digitally and by restoring and using analogue filters, custom-built by Otto Kränzler for a performance in the 1980s.

Paolo Brenni & Roland Wittje: The singing arc and the speaking arc

Around 1900, carbon arc lamps were widely used for street lighting and as projection lamps. They created light using an electrical arc between two carbon electrodes. These lamps often produced audible humming, hissing, or even howling sounds. The British physicist and electrical engineer William du Bois Duddell (1872-1917) in London and the German physicist Hermann Theodor Simon in Göttingen (1870-1918) managed to tame the hissing of the electric arc and actually made it speak, listen and sing. Its capacity to produce rapid electric oscillations combined with its function as a loudspeaker and microphone made the carbon arc a perfect candidate for wireless telephony through electric oscillations waves. The speaking arc, however, never made it beyond its existence as a lecture demonstration and remained a laboratory curiosity. On the other hand, another device, the amplifier tube, fulfilled the arc’s promises of sound amplification and wireless telephony.

A few years ago, we could reproduce several demonstrations with the electric arc using the original apparatus made at the beginning of the 19th century by the firms Max Kohl and Ernst Ruhmer and today preserved at the Fondazione Scienza e Tecnica in Florence. Making the arc speak or listen to us proved to be more challenging than we expected. As it is often the case, rather than giving answers, re-working the apparatus opened up for a whole new set of questions that did not arise from our previous reading and interpretations of the written and material sources. Operating the electric arc provided new experiences of what electroacoustics could be far away from the domestic hi-fi electronics.

13:00 Lunch break

14:00 Panel III: Performative experiments in early cinema and gaming

Stefan Höltgen & Shintaro Miyazaki: Tennis for Two

A short video about the first electronic video game called “Tennis for Two” and its re-enactment by Stefan Höltgen and his students at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. We will talk about our ideas, approaches and methods concerning what you might call performance and dissemination of media-archaeological experiments and its media theoretical implications.

Martin Loiperdinger: Crazy Cinématographe – Early Cinema Performed on Luxembourg’s Schoeberfouer

From 2007 to 2011, for three weeks in August and September, 35mm short film programmes of roughly 20 minutes each have been performed in the environment of Luxembourg’s Schoeberfouer in a tent cinema called Crazy Cinématographe. These early fairground cinema revival shows included all performative elements of live accompaniment that were usual before the First World War: live music, bonimenteurs, and front show to draw patrons into the tent. Crazy Cinématographe was an experiment in media archeological practice – taking place not in a lab, but in today’s cultural space where cinema was established in its first two decades. Crazy Cinématographe originated within the framework of the European Capital of Culture project “Travelling Cinema in Europe” in 2007 as a project of the Cinémathèque Luxembourg, conducted by Claude Bertemes and Nicole Dahlen. The programmes of 2007 were curated by Vanessa Toulmin. Unfortunately, only the last edition of Crazy Cinématographe has been documented on video, by the University of Trier. I will present and comment on an extract showing the 2011 Crazy Cinématographe performance of Winsor McKay’s Gerti the Dinosaur.

Annie van den Oever: The Lecture Performance as an Education Tool in the Field of Early Cinema. Lessons Learned from Art History

15:15 Break

15:30 Panel IV: Protocols of historical re-enactment in medical anthropology, surgery and fine arts

Maartje Stols-Witlox: The role of environment: Re-performing a historical recipe in two different settings

In this presentation, I would like to reflect on lessons learnt in an experiment where I re-performed a seventeenth-century recipe to make a varnish twice in two distinctly different settings, the first a clean laboratory setting, the second a more ‘historically appropriate’ setting. In the field of art conservation, re-enactments are used to learn about the properties and application of historical materials. The field’s focus on material – and the strong voice of the natural sciences in our field, and their influence on how re-enactments are approached, executed and interpreted, call for reflection.

Anna Harris: Testing fields of view: Re-enactment as methodological probe in ethnographic fieldwork

Anthropologists tend to study those who engage in re-enactment practices, rather than use the methodology themselves, however there is a growing trend in ethnographic experimentation which delves into this exciting work (for example the work of Brazilian artist-ethnographer Veridiana Zurita who films Amazonian families re-enacting scenes from their favourite soap operas, the insights into their lives generated from the ways in which they adapt and add flourish to the scripts). Drawing inspiration from our collaboration with historians, the Making Clinical Sense research team used re-enactment in various ways in our study of how medical students learn the sensory skills of diagnosis. We found it particularly useful in documenting our learning of embodied skills, skills which we found both hard to articulate without performances. We were also trying to grasp details of how we learn that eluded us without documentation, and re-enactment become one way we could do this – filming ourselves perform a skill we had just learned in class for example. In this presentation I will show a video of myself re-enacting one of these skills, the skill of testing visual fields. My approach to re-enactment is playful and somewhat ahistorical. I see it as a methodological probe for ethnographic enquiry, particularly important for a team-based and comparative project, through material engagement with artefacts and practices in our fields of study. I look forward to developing these ideas further with experimental media archaeologists, historians and others engaging in re-enactment experiments in this workshop.

Roger Kneebone: Documenting the early days of keyhole surgery through simulation-based re-enactment

Minimally invasive (‘keyhole’) surgery was pioneered in the 1980s, heralding a radically new approach which transformed surgical practice in the decades which followed. The urologist John Wickham, leading a creative team of clinicians and design engineers, played a leading role in these developments, though his contribution remains under-recognised. He and his colleague Mike Kellett (an interventional radiologist) performed the UK’s first percutaneous nephrolithotomy (removing a urinary tract stone through a small skin incision under X-ray control). Their innovative work went on to revolutionise surgery, and its reverberations continue to this day.

This project set out to document the processes, embodied practices and collective ‘ways of doing’ of this group of professionals as they broke new ground in their field. The Wickham team (most of whose members had long retired) was invited to come together in the London Science Museum to re-enact procedures from that time, using physical simulation. Procedures were captured using video, and interviews with participants recorded the insights and recollections which these re-enactments prompted.

This presentation will show selected footage from this work, inviting discussion about simulation-based re-enactment as an approach to historical enquiry into events which remain within living memory.

John Wickham died in 2017 at the age of 89.

17:00 Break

19:30 Panel V: Media Archaeology Labs

libi striegl & Lori Emerson: Frequency

The Media Archaeology Lab as experienced in the frequency ranges of 500-1100kHz and 30mHz to 3GHz. Demonstrating our collection of over-the-air transmission and reception devices, and considering the impossibility of a visual demonstration of the invisible.

Erkki Huhtamo: The Astronomical Lantern – a Forgotten Chapter in the History of Mobile Media

Paul DeMarinis: “How to cut a faulty record from a plastic picnic plate“

20:20 Break

20:30 Closing discussion