What approaches, methods and techniques are there for documenting historical re-enactments and experiments? Which best practices and “artful failures” can we distinguish? What documentation tools can we use, what are their affordances and limitations? How can we learn from other disciplines in documenting hands-on experiments? What are the epistemological and methodological opportunities and challenges of doing experimental historiography and archaeology? By addressing these fundamental questions, the DEMA project team organized a two-day workshop to reflect on, share and exercise documentation practices in hands-on experimental research. One of the aims of the workshop was to contribute to the development of a best practice guide and protocol that we can use for documenting our media archaeological experiments in the DEMA research project.[1]

DAY 1

DEMA advisory board meeting

The DEMA workshop was preceded by the project’s first Advisory Board Meeting. DEMA advisory board members include: Professor John Ellis, media theorist and historian at Royal Holloway University of London; Associate Professor Lori Emerson, media archaeologist and founding director of the Media Archaeology Lab at the University of Colorado, Boulder; Professor Erkki Huhtamo, media historian and theorist at UCLA; Professor Martin Loiperdinger, film historian at Trier University; and Professor Annie van den Oever, film theorist and founding director of the Film Archive and Media Archaeology Lab at the University of Groningen. With the advisory board members, we discussed the project plans, the two post-doc research projects within the DEMA project and a “best practice guide” for doing media archaeological experiments that we aim to develop.

In his introduction to the advisory board meeting, Andreas Fickers, as DEMA’s Principal Investigator, outlined the origins and objectives of the project. The idea of creating an experimental media archaeology (EMA) builds on activities that have been realised at C2DH during the past years and is also the result of cooperation with practice-led researchers such as Annie van der Oever, John Ellis and Ludwig Vogl-Bienek. It seeks to challenge the approach to classical media archaeology which has been to a large extent excessive in discourse analysis rather than with practical or hands-on historical enquiry. In EMA, critical thinking is combined with hands-on tinkering; a mental, physical and sensorial grasping of things, or “thinkering” – a term coined by Erkki Hutamo[2] and often used at the C2DH to promote the idea of playful and experimental ways of doing media history. EMA has been developed on a theoretical level in several articles.[3] Its aim is to de-auratise historical objects, by handling, operating and experimenting with them, learning through failure as much as by success and to turn historians and researchers into experimenters, not only neutral observers. To this end, C2DH has already hosted a number of hands-on experiments with, for example, the Magic Lantern and the Edison Phonograph. What is missing though, is a means to make these experiences somehow explicit through documentation. How to describe the hands-on activities and how we learn from them? How to translate those sensory perceptions or bodily experiences into written expressions or through audio-visual documentation? How does this differ from only studying texts, film or sound on their own? In this way, EMA takes inspiration from other fields, including experimental phenomenology and sensory ethnography.

DEMA objectives

One of the main objectives of the DEMA project is the development of a protocol or “best practice guide” for documenting the hands-on experiments so as to produce data and information that may be shared by those interested in engaging in similar kinds of activities. Some key questions include: Is there a best way of documenting hands-on experiments in order to make them useful for others to replicate such experiments in research and teaching environments? What does it mean to reproduce an experiment in a different setting? Under scrutiny in the DEMA project is the role of the re-enactment and its importance as a methodology in studying media history. The terminology may differ. For instance, in the context of the ADAPT research project on analogue television production, John Ellis prefers the term “re-doing” or “simulation”, to re-enact the action rather than a specific moment in history.[4] In the DEMA project we are building on the tradition of historical re-enactment, however, this project seeks to systematise the practice of re-enactment, to develop, define and document a variety of hands-on experiments.

Experimental system

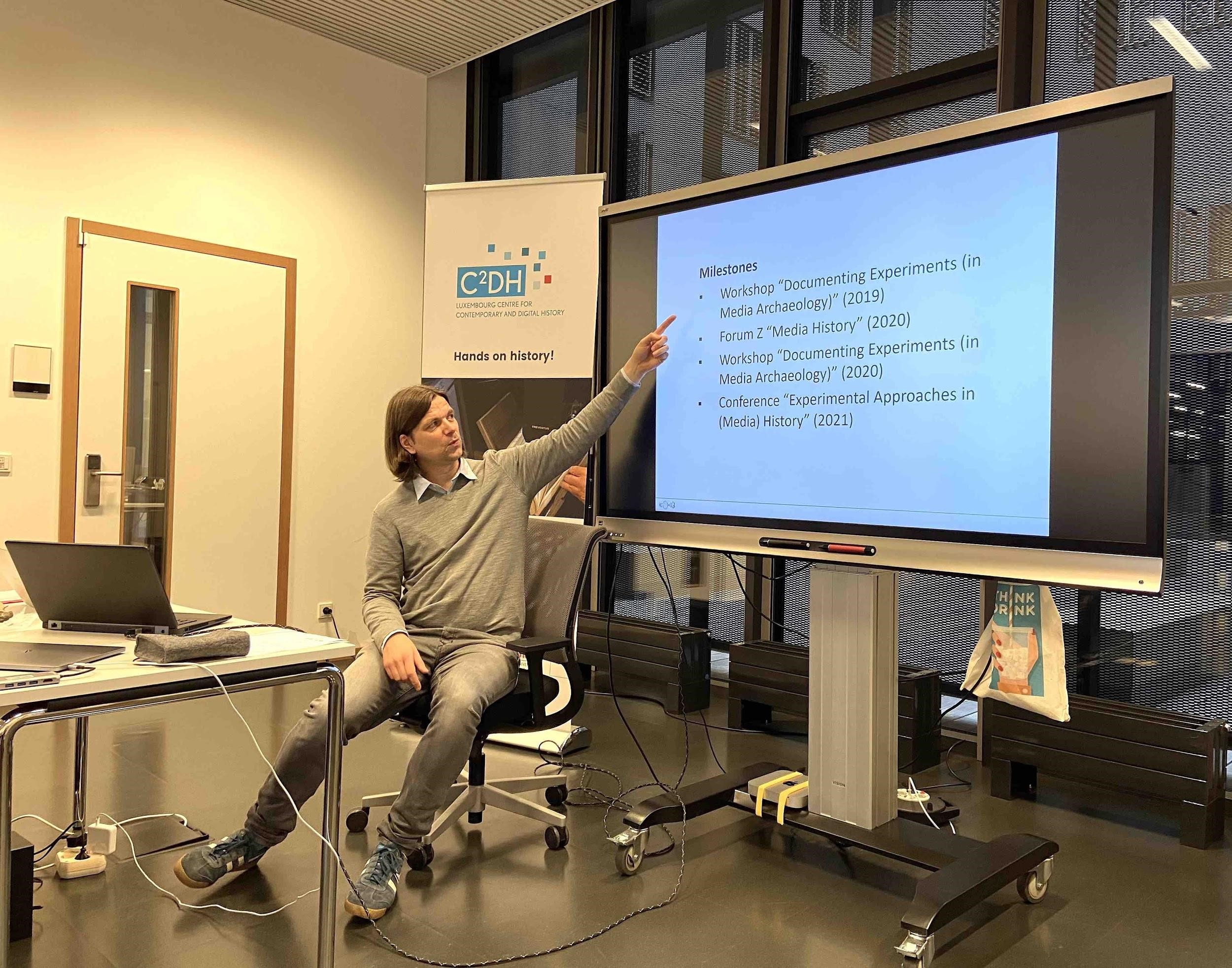

DEMA coordinator Stefan Krebs outlined the different types of experiments that will be carried out during the course of the project. One of the main inspirations in devising these experiments comes from scientific research, namely from the work of Hans-Jörg Rheinberger and his concept of an “Experimental System”[5] In it, we are asked to question how an experiment helps us to discover something that is not even known to the experimenters. Rheinberger reminds us that the epistemic status of the objects under study very often changes from epistemic objects to technical ones, depending on the perspective of the researcher and the questions being asked during the experiment.[6] Conversely, a technical object, or instrument, may become an epistemic object during subsequent studies and can therefore raise further questions. This idea of the changing epistemic nature of things under study equally applies to the media technologies that we are examining in our project. With this in mind, we have devised a system that employs three types of experiments: “basic”, “media-technological” and performative” experiments.

In our basic experiments, the technologies themselves are the epistemic objects; their functionality, frequency range or luminosity is tested, their properties are examined. The media technological experiments involve handling and usage. In the last stage of performative experiments, we will simulate or re-enact performances or situations that are close in their original context of use. The results of these experiments will be used to inform the aforementioned best practice guide. Other milestones of the DEMA project include various public demonstrations of our media archaeological experiments, a Forum-Z event that involves the wider public, a second workshop focusing on performative experiments in media archaeology, various academic publications, and a final international conference.

Post-doc research projects

The DEMA project includes two post-doc research projects, focussing on two different sets of media technologies as use cases, one visual and one auditory.

In his presentation, Aleks Kolkowski outlined his DEMA projects that focused on historical sound recording and reproduction devices. These include the reconstruction of a compressed air-assisted Auxetophone Gramophone, circa 1906, used to play disc records at greatly increased volume, e.g. in the open air and in combination with live instruments, and also for the amplification of stringed instruments. The reconstruction project is being achieved through a collaboration with the Science and Engineering department at the University of Luxembourg’s Kirchberg Campus and the aim is to construct a working model that may be operated and tested in experiments that would culminate in historical re-enactment of an Auxetophone concert performance with live musicians. Two further projects examine recording devices, namely a portable disc recording apparatus, the HMV 2300H (1949) suitable for small studios, and the Wilcox-Gay 1C-10 combined magnetic tape and disc recorder (1951), an unusual hybrid device that allowed for recording and playback across distinct formats. The HMV 2300H was obtained together with all the contemporary accessories and blank media necessary for recording; complete service records, service manuals and documentation – an unusually complete acquisition and an ideal assemblage for the purposes of research. The Wilcox-Gay 1C-10 is a highly interesting device as it attempted to integrate the system of recording onto tape and mastering onto a disc in one unit. It was designed for the semi-professional user and touring or practising musicians for making demonstration recordings. The multiple functionality of this machine makes it ripe for experimental research into its practical usage.

Feedback from the panel included questions about the contemporary responses to the Auxetophone technology; the awe and astonishment that greeted it has parallels with early cinema. The type of media or discs used with the device was discussed as well as ’sky shouting’ technology, developed at the end of World War One, where the Stentorphone, an offshoot of the Auxetophone (also being reconstructed in this project), was used for air-to-ground communications on aircraft in trials by the RAF. It was proposed a “comparison concert” be staged in order to compare the efficacy of different sound reproducing technologies. An advertising brochure shown mentioning the HMV disc recorder used in a car to determine the amount of noise produced by the vehicle at different speeds also brought parallels with the scientific uses of cinema technology. It was proposed to re-enact this type of experiment as part of the programme.

In his presentation, Tim van der Heijden outlined his DEMA post-doc research on the topic of early-twentieth century home cinema.[7] Drawing on his PhD research, which investigates the home movie as a family memory practice from a long-term historical perspective, the current project compares two dispositifs of early-twentieth century home cinema in particular. The first home cinema dispositif deals with the Kinora, a motion picture technology from the 1900s and 1910s that was specifically designed for home use. The Kinora viewer functioned like an individual viewing machine that made use of a flipbook mechanism, in which a series of paper-based unperforated photographs were attached to a wheel. By turning the wheel and looking through the viewer, one could watch the series of photographs in motion. The Kinora home cinema dispositif will be compared to the home cinema dispositif of the 1920s and 1930s, when the recording and projection of moving images domesticated and popularized as a family practice after the release of the Pathé 9.5mm and Kodak small-gauges and their accompanying film equipment. The media archaeological experiments in the project aim to compare and reconstruct how the Kinora and small-gauge technologies worked and how they were used. Several objects will be central to the experiments, including an original Kinora viewer from ca. 1907, various Kinora reels, a hand-cranked and motor-driven Pathé-Baby projector, various 9.5mm and 16mm film cameras and a number of amateur filmmaking accessories. In addition to these experiments, the project furthermore aims to make a working replica of the rare Kinora camera in collaboration with the Science and Engineering department of the University of Luxembourg, the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, U.K. as well as various international experts.

Responses from the advisory board panel began with a discussion on the shift in dispositif of the Kinora to the Pathé Baby projector; namely, the practise of viewing in so-called “peep mode” – by only one viewer – versus images projected on a screen and watched by multiple viewers. Aside from the types of screenings, it is important to consider the relationships between the technology employed, the content and the viewer’s perception and relate them to different user practices. Therefore, the subject is examined not only in terms of screening but also with regard to its recording or filming, as well as the materiality of the media; how, for example, the paper-based photographs used in the Kinora, shape user practices. In a discussion of amateur practices, it was posited that early home projections were themselves reenactments of professional public screenings, with the father often acting as the master of ceremonies and projectionist. Individual experts and institutions were mentioned as sources of information and for possible collaboration as well as collectors and collector societies. The question of documenting “how you learn how to learn” was raised, and also how one incentivises those with whom we seek to collaborate, such as technicians, collectors, expert repairers etc. As a rule, such collaborators are deeply interested in the work and so offering an incentive is not usually a problem. C2DH will be launching a new journal for digital history, a hybrid publication with opportunities for transmedia storytelling and within it, there will be scope for representing the tacit work contributed by collaborators on our projects by means of video or audio recordings.

Best practice guide

The final part of the DEMA advisory board meeting included a discussion on the topic of a best practice guide for doing experimental media archaeology, a key element of our overall project. Determining the target beneficiaries or audience is an important first step but the value of such a guide is perhaps most evident in terms of teaching students how to do practical media-historical research, in showing how similar experiments may be replicated and performed in classrooms and teaching spaces using the protocols and methods of documentation that we put forward. Tim van der Heijden went on to describe a best practice guide created within the research project “Changing Platforms of Ritualized Memory Practices: The Cultural Dynamics of Home Movies” in 2015, which is called “Het Behouden Waard” (Worth Keeping). Aimed at amateurs, collectors, families and everyday users, this guide shows how best to preserve films on various media formats: from cine-film and video tape to digital video. The online guideline was made in collaboration with the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision and was hosted by the Institute’s Amateur Film Platform. It took its inspiration from several ‘how-to’ guides, such as the Library of Congress guide on personal archiving. While most of these sites focus on the technical aspects of preservation, the Worth Keeping guide encourages the addition of contextual information that is so crucial for historians and researchers to better understand the past. This particular best practice guide is intended for non-expert users who have personal material they wish to preserve for future generations and who perhaps do not own the technologies needed in order to screen the films or videos.

For the DEMA best practice guide, we discussed questions related to structure of the guide and the steps needed to follow in order to perform experimental media archaeology, including preparatory work and research, the different types of experiments and their documentation and the recommended tools for successful documenting. It was proposed that the guide be embedded among the nascent international networks of experimental media archaeology (such as the RRR Network) in order to reach academics and practitioners involved in doing and teaching media archaeology. The DEMA project looks at only a small selection of media, for a best practice guide to be comprehensively applied in practice it would need to deal with a larger variety of media technology and their dispositifs, audiences, users and producers. Therefore, the DEMA guide may only be applicable to a limited range of subjects, primarily in the analogue realm. However, a guiding set of principles for performing experiments in media archaeology is a very much needed and useful aspiration. There are differences in dealing with pre-electronic mechanical objects, where the workings are visible and possible to intuit, compared with electronic systems that require particular skills and knowledge to fully comprehend.

A guide that can address different kinds of users including non-specialists is desirable. More difficult to include or address in the guide are objects in the digital realm and in internet culture such as gaming, digital animations, meme creation and the activities of cosplay communities to name but a few. This is primarily user-made content and participatory media that is worth preserving, however, can digital culture be included or how could the DEMA best practice guide be relevant to these types of digital media? Determining the audience for the guide is highly relevant; is it intended for those interested in preservation or repurposing, halting the tide of electronic waste or documenting media technology of the 20th century, the conditions of its production, the different actors involved in using the objects? These are fundamentally different interest groups but all have a place in education. It was stressed that an important part of studying media archaeology is to take into account the cultural reception and impact of technologies, especially with regard to mimetic media, and examining the sensorial, performative, experimental and perceptual value of the objects we examine. In the DEMA project, we plan to make performative experiments which are designed to address all these aspects. At the same time, we will examine source materials, from those aimed at expert users typically found in technical journals to the configured user seen in contemporary advertisements. The approach asks for a more systematic reflection on how historians tell their stories, prefigured by the sources they use and promotes the idea of shared authority in digital public history, collaborating with collectors, amateur users and independent researchers.

A best practice guide might also encourage practical research into objects of media culture that have hitherto been neglected, unidentified as being of interest. An example worthy of investigation is the sound postcard, a medium which enabled sounds and recorded messages to travel over postal networks and one that could well serve this media archaeological cause. As every media object might demand its own unique set of best practices, could the guide be user configurable, and in terms of documenting experiments at what level should it be carried out? Projects such as ADAPT which are highly professional in terms of their documentation, might make people shy away from documenting their hands-on work, while the plethora of “how-to” guides online made by non-professionals would suggest otherwise. The acquisition of objects for media archaeological experiments might be a good starting point for a best practice guide, there should be little difficulty in obtaining emblematic objects such as magic lanterns, stereoscopic viewers or phonographs, where they were manufactured in their thousands, through auction sites. Advice on repairs and restoration made be given, however, it is not intended as a guide for preservation or conservation purposes. In addition to collaborations with collectors and amateurs, the involvement of artists in the project was advocated as playing an important part in the DEMA project, informing best practices and experimental work. Paul DeMarinis and Toshio Iwai were cited as examples of leading artists whose research methods and artworks show close links with media art practices and experimental media archaeology.

In closing, the term “best practice guide” was debated, but no alternative was put forward other than to strike “best”. However, it was defended as a means of systematising what many have found on the way to doing their experiments. What is ideally needed is a guide for teachers to implement within a curriculum at any level, from training researchers to first-year undergraduates. A goal should be to make it simple for people to perform media archaeological experiments so that they actually do them. Reports on experiments and lab diaries should also document failures as well as success, in particular, learning from Rheinberger, who attempted to develop a system that allowed him to document historical scientific experiments in the same way as he had previously done in a modern biology lab.[8]

Opening DEMA workshop

In the afternoon, the DEMA workshop officially started. In addition to the five advisory board members, we welcomed Emeritus Professor Falk Rieß (University of Oldenburg), Dr. Wolfgang Engels (Histex GmbH / University of Oldenburg), Associate Professor Leslie Carlyle (Universidade NOVA de Lisboa), Professor Julia Kursell (University of Amsterdam), Professor Benoît Turquety (University of Lausanne), Dr. Ludwig Vogl-Bienek (Philips Universität Marburg), Karin Bienek (Illuminago, Frankfurt), and Dr. Tim Boon (Science Museum London) (present via Skype).

After a brief welcome round, Andreas Fickers gave a short introduction to the DEMA project and explained about the purpose of the workshop. One of the aims of the project is to think about a methodology of how to do media archaeological experiments and how to document these experiments in such a way that they can be useful for others in both research and teaching environments. The question is therefore: how can we sensitize not only ourselves, but also future generations of media historians to the many implicit forms of knowledge that are into the handling of historical media technologies? And how can we make this explicit through documentation? The objective of the workshop is to bring people together from different fields – including experimental archaeology, media history, art history, musicology, and the history of science – to exchange ideas and learn from each other’s experiences in documenting, doing and sharing hands-on experiments.

Lessons learned

The DEMA advisory board members started by presenting their lessons learned based on previous or ongoing projects.

John Ellis (Royal Holloway University of London) generously shared seven lessons from his experiences in ADAPT, a television history research project which explored the history of analogue television production by means of historical re-enactments. Between 2013 and 2018, the project team carried out a series of historical “simulations”, in which they brought together retired television producers with now obsolete television production equipment, including flatbed editing tables and electronic broadcast cameras. John’s first of his lessons learned was that museums often don’t have working examples of the historical media objects, but they do have access to a broad network of collectors, maintainers, tinkerers and enthusiasts, including retired professionals. These people are invaluable for your project. However, it may require good communication skills to make them collaborate and understand the purpose of your project.

It is furthermore important to understand that doing hands-on media history is not just about excavating the memories of past users, like in an oral history project. The encounter they have with the material in the historical reenactments can bring new memories to the fore, including bad memories (e.g. when something went wrong). Reenactments therefore involve a different form of remembering, which can even dislocate established memories. Another lesson learned is that technological machines are not isolated as historical objects, but their user practices involve hidden or disappeared infrastructures. Tracing not only the historical objects, but also their infrastructures should therefore be part of the media archaeological work.

Furthermore, documenting the hands-on experiments usually requires a high level of file organization and data management. In the case of the ADAPT project, more than 16 TB of audiovisual footage was generated, including the editing of more than 160 videos. Using 360 degree video recording technologies can be useful for documenting experiments, because they are less intrusive (compared to traditional cameras) and moreover allow for interesting virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) applications. For analyzing the audiovisual footage, which can be very difficult and time consuming, the advice is to include ways of referencing back to the material. Or to develop a way to search and annotate the footage, for instance by means of artificial intelligence software. A final lesson learned is less directed to the media historian, but to the museum and archival world: collection acquisition should always include the video-recording of a demonstration or interview with the donor, who knows the story of the object, or an expert user. For the media historian, documenting this information is often as valuable as preserving the historical object itself.

As part of her lessons learned, Lori Emerson reflected on the Media Archaeology Lab (MAL) of the University of Colorado in Boulder. As founding director of the MAL, Emerson first presented a brief history of the lab and how it has the largest collection of media technologies worldwide, providing access to 1000s of items of still functioning media technologies, ranging from the late 19th century until the late 20th century. Visitors of the MAL are encouraged to actively tinker and experiment with the historical media objects. Besides researchers and students, the MAL also works with artist residencies to emphasize the point that the objects are meant to be used. In that sense, the MAL functions not like a museum, in which the objects are often behind glass, but more like an “anti-museum”. Currently, 12 volunteers and 4 PhD students are working for the MAL.

In terms of documentation, Emerson tried several things. One of the barriers for a systematic documentation of the hands-on teaching and research activities that are being conducted in the MAL, is that every technology is different. Good documentation is labour intensive and time consuming, while currently there’s no incentive for students to do this. Instead of writing lengthy white papers, MAL now asks visitors to write a short technical report – called “MALware Technical Reports” – for the lab’s website and newsletter. These reports, according to the website, “document events, research, teaching, and artist residencies taking place in and through the lab.” Nobody wants to document, but if we don’t want to engage in blackboxing, Emerson argues, documenting hands-on activities is crucial!

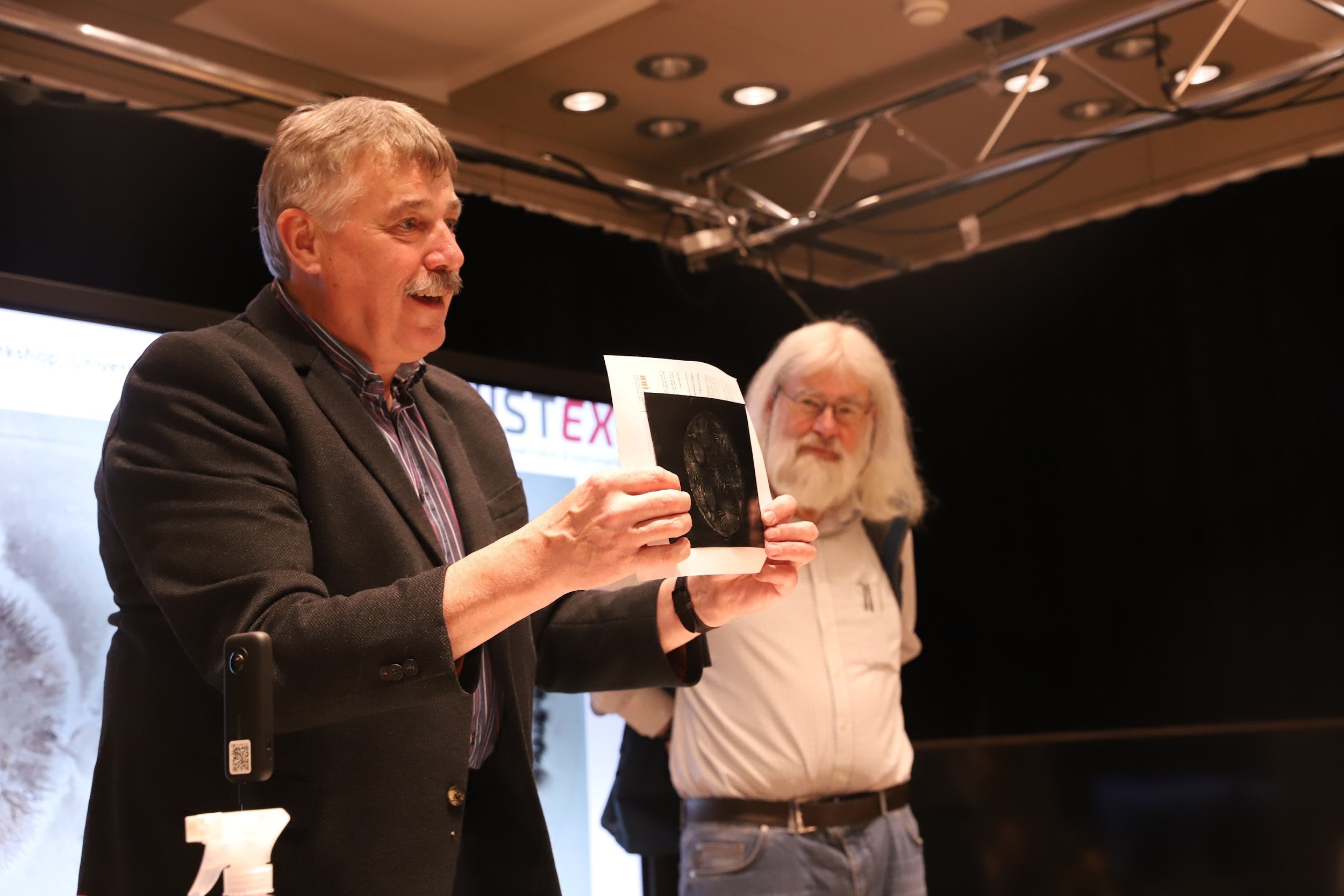

In his lessons learned, Erkki Huhtamo emphasized the importance of exploring media objects not only through discursive analyses – like in his media archaeology as topos study – but also by showing how to practice media archaeology with the objects themselves. Being a pioneer in the field of media archaeology, over the years Huhtamo has besides studying media historical objects also established a special collection of early 18th century to early 20th century optical media technologies, including rare magic lanterns and early motion picture devices. One of the objects from his collection that Huhtamo has been studying, both in terms of its technological history as well as the discourses around it, is the Spirograph. This very rare and forgotten media device, an early moving picture technology that “utilized spinning discs on which microphotographs were arranged in a spiral,” was innovative in the early 1900s. Although the Spirograph was meant as a radical departure from existing forms of moving picture technologies at the time, Huhtamo showed, it became an example of a “failed moving picture revolution”.[9]

Devices like the Spirograph are interesting for doing media archaeological experiments, but they also have their limitations. First of all, researching a device this way is very work intensive. Huhtamo’s study of the Spirograph took him almost ten years. Secondly, the “hardware” (i.e. the device’s housing and internal mechanism) can be very fragile and the “software” that the device once used (i.e. the spiral disc with the microphotographs in the case of the Spirograph) can be deteriorated and so no longer accessible. The only way to research and demonstrate the device, Huhtamo argues, is to disassemble and reassemble it – literally opening up the “black box”. Such a hands-on approach is crucial for getting a better understanding of how the device used to work in the past.

Besides giving such hands-on demonstrations to students and researchers, which he welcomes to his personal collection, Huhtamo has also been giving public performances with some of his 19th century magic lanterns, among others in Los Angeles and Japan. While he uses original lantern slides and equipment in these shows, he is not acting as a 19th century showman but rather performs a “role play” as a contemporary researcher in order to create a reflexive dialogue between the past and the present. More recently, he has also been making video demonstrations for a YouTube channel in which he applies experimental media archaeology to the objects of his own collection, called “Professor Huhtamo’s Cabinet of Media Archaeology”. In these videos, Huhtamo is demonstrating the devices and gives some explanations about their cultural significance. Doing hands-on investigations, Huhtamo concludes, is extremely important, but when doing this we should always take the historical dispositif into consideration as well. In that sense, a discursive (i.e. topos) and hands-on approach to media archaeology could well go hand in hand.

In her lessons learned, Annie van den Oever shared some of her experiences as head of the Film Archive and Media Archaeology Lab embedded in the University of Groningen. The collection holds over 2000 film reels, but Van den Oever refocused on the technological apparatuses in particular, so the archive would become a laboratory for doing hands-on experiments. Many film scholars, she noticed, never touch the technological devices, but rather live in a “world of books”. It inspired her to invite first-year students to the Film Archive before they start reading about film as a medium and technology. The aim is to let the students experience the technologies by handing the film historical objects from the archive’s collection – a 70mm film reel, a 16mm Bell & Howell Filmo camera from 1937, a Zeiss Ikon 35mm projector – so they can touch it, look at it, and subsequently start asking questions about it. Handing students these objects, rather than giving lectures or explaining about them, is very stimulative in this regard. It allows students to feel the weight of the camera, smell the vinegar syndrome (caused by the film’s acetate base degradation), hear the sound of the Maltese cross and the flapping of the projector’s shutter, which is very loud and therefore raises questions about cinema’s silent era.

After these encounters with the historical devices, Van den Oever’s students go to a room without equipment. Sitting there, they are asked to draw the object that they have just seen and touched based on their memories. Interestingly, Van den Oever found that while most of the students have never seen the object or read about it before, they are able to recall quite a bit of its details. More importantly, using the hands-on approach as a didactic tool works on their imagination and so leads them to ask different types of questions than before. Working with the collection in a hands-on manner, in other words, “kick-starts” their reading and even creates a different type of relationship to the film historical source materials. These examples demonstrate the heuristic value and potential of a hands-on and sensorial approach – the touching, feeling, smelling, and the trying of technological devices and replicas – in teaching film studies.

DAY 2

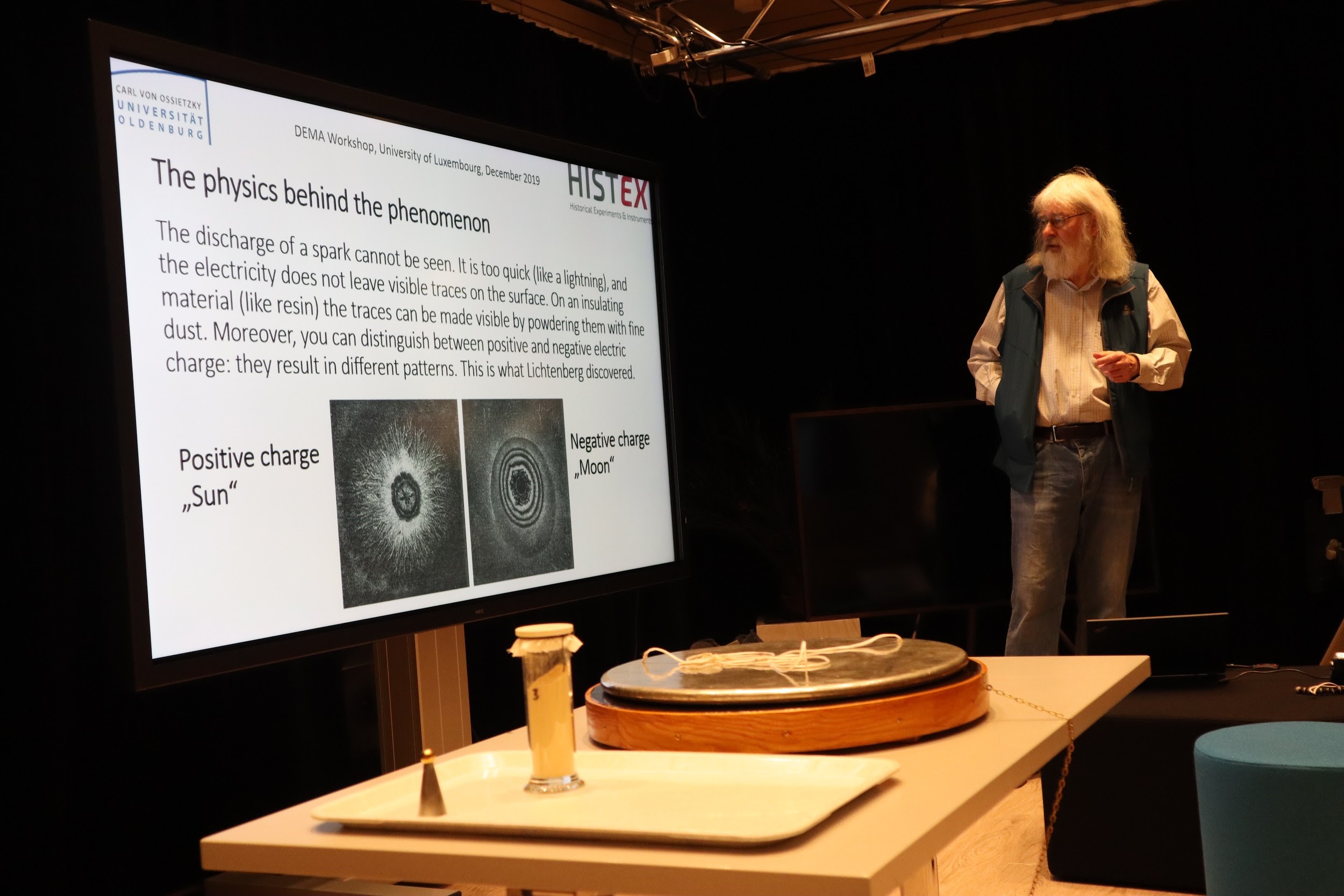

Images of invisible traces: a hands-on practical experiment

The second day of the DEMA workshop started with a historical re-enactment of an 18th century physics experiment, led by historians of science Falk Rieß and Wolfgang Engels from the University of Oldenburg. In their presentation, entitled “Images of invisible traces: The repetition of historical experiments producing (and reproducing) Lichtenberg figures”, Rieß and Engels gave a demonstration of this ground-breaking physics experiment on the uncovering of electric discharge patterns and attempts to preserve the results by means of different methods, both antique and modern.

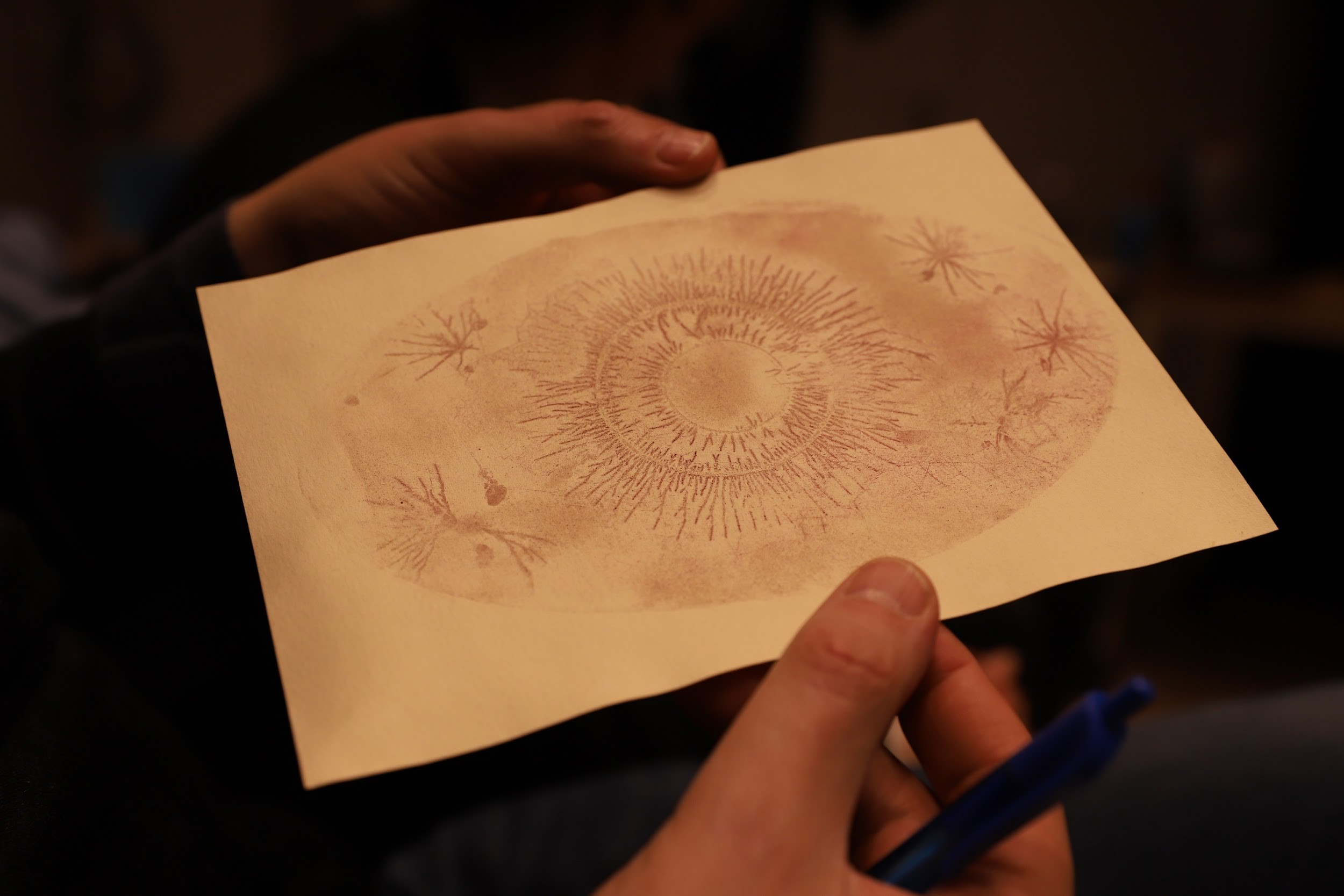

They started by giving a short history of the phenomenon, and the persons that played a decisive role in its development. The central historical figure is Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799), a physics professor in Göttingen, who with the help of his assistants Johann Andreas Klindworth (1742-1813) and Johann Hermann Seyde (?-1813) experimented with ways of transferring and preserving energy. The instrument that he built, called the “electrophorus”, consists of an isolated plate of resin that was used to generate electricity through induction. Initially, Lichtenberg thought that the electricity relocated to the resin plate would not fade away. But when he wanted to make the resin surface of the electrophorus more flat by grinding it, he found out by accident that some beautiful figures arise when wiping away the dust collected by the resin plate:

“My room was filled with the finest resin dust from the production of an electrophorus. When the dust fell on the lid of the electrophorus it formed stars and suns. The figures had wonderful tiny twigs.” (Lichtenberg in 1777, translated from German into English by Falk Rieß)

Lichtenberg’s discovery led to a series of experiments to better understand where the figures came from. In their demonstration of how to make electrical discharge patterns, Rieß and Engels explained the physics behind the phenomenon:

“The discharge of a spark cannot be seen. It is too quick (like a lightning), and the electricity does not leave visible traces on the surface. On an insulating material (like resin) the traces can be made visible by powdering them with fine dust. Moreover, you can distinguish between positive electric charge (“sun”) and negative electric charge (“moon”): they result in different patterns. This is what Lichtenberg discovered.”

Producing Lichtenberg figures as historical experiment

After the demonstration, participants were invited to a hands-on exercise in which they recreated the electric discharge experiments and made their own Lichtenberg figures at their own working tables. They were also asked to document the process in detail and to reflect on how performing the experiment is similar and different from the times when Lichtenberg was doing it, more than two centuries ago. Afterwards, we discussed the experiences of the participants. One of the things that is different from the times of Lichtenberg is, of course, that we now know the effects of electric discharge, which creates a whole set of expectations around the experiment. We know in advance that this will happen, whereas Lichtenberg didn’t know the outcome of his experiment. This subsequently raised the question whether it was actually an experiment that we did, or a reproduction of an experiment? Or perhaps just the learning of a certain technique by trial and error? What makes an experiment experimental? Is it the uncertainty of the results, that you don’t know the outcome beforehand? In that case, the workshop was rather a reproduction of the experimental process, which nonetheless enabled participants to develop tacit knowledge in making the Lichtenberg figures with the same methods and materials of the time.

Furthermore, the experiment made participants reflect on their own documentation practices, or rather their lack thereof. Nearly all of the participants started doing the hands-on experiments right away, but completely forgot about dividing roles between “experimenter” and “observer” in the process, as is standard practice in most physics laboratory work. Because they failed to systematically document the process, for instance, one group couldn’t understand the different outcomes between their first experiment, which was a failure, and their second experiment, which produced more satisfying results. Doing the experiments and documentation at the same time can be rather challenging. One of the participants argued that it keeps you away from a certain “rhythm”, because after you do something for the first time you have to repeat it in order to write down what actually happened. This dynamics between experimentation and documentation seems crucial when thinking about a methodology for experimental research. When starting to document the experimental process too quickly, another participant argued, the documentation itself may become the “epistemic thing” rather than the object of study. A solution might be to divide between tasks here and, additionally, to do a “thought experiment” first to imagine what would be the salient points of the experiments. By hierarchizing the elements of the process, it becomes more clear to know beforehand what to document and what not. On the other hand, such thought experiments can also create certain expectations which makes the researcher less open for “the unexpected”.

The question of documentation finally led to a discussion about the different means of documentation. When we record everything with a 360 degree camera, for example, are we actually documenting? Or does the documentation process imply an analysis of the material as well? One difference between documenting by means of taking a photo or making a video and documenting by means of taking notes is that the latter already includes some form of reflection and digesting of the experience. One of the advantages of the raw photo and video material, on the other hand, is that it enables you to retrace your steps more efficiently than when you take notes based on what you assume will happen. Photo and video documentation enables you to catch certain physical techniques that are often very difficult to verbalize, John Ellis argued based on his experiences in the ADAPT project. By including the thought process on video, for instance by verbalizing certain actions and thoughts, you can capture both the action process and the reflection of the experience at the same time. Documenting the experiments this way helps to make the video footage more analytical.

Making imprints of Lichtenberg figures

The second part of the hands-on workshop was all about how to document the Lichtenberg figures themselves, so as to make a perpetual imprint of them. Although Lichtenberg himself has tried to make imprints of the figures, it was Adolph Traugott von Gersdorf (1744-1807) who mastered the aesthetic process of reproduction. Von Gersdorf, a squire and amateur scientist, made more than 1400 imprints of the Lichtenberg figures, some of which have remained and are now part of a museum collection in Görlitz, Germany. Like Lichtenberg, von Gersdorf had an assistant: Christoph Nathe (1753-1806), a painter and graphic artist. Instead of drawing the figures, they developed a method for making the imprints which required a special type of paper and glue, i.e. thick milk mixed with casein. The procedure for making the imprints includes the powdering of the plate, the preparation of the paper and glue, rubbing the paper by a spoon or by hand on the plate, and then removing the paper from the plate, after which the imprint of the Lichtenberg figure appears. After a short demonstration by Wolfgang Engels, the participants could make their own beautiful imprints of their Lichtenberg figures. It allowed them to create a nice souvenir of a fascinating workshop, which truly combined theory and practice, experimentation and documentation, science and art.

Provocations on documenting experiments

In the afternoon, four workshop participants presented short ten-minute provocations.

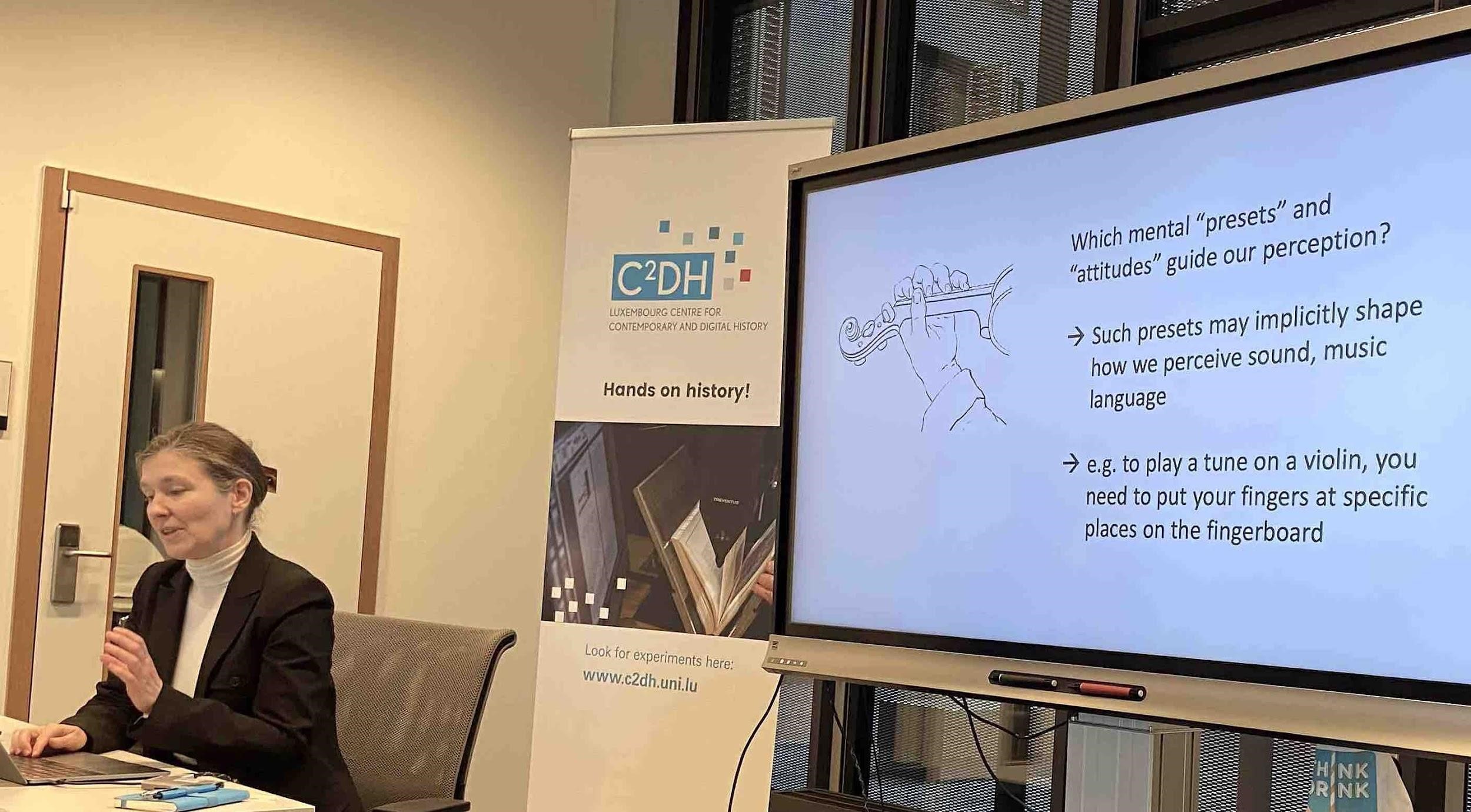

In her presentation, entitled “Documentation and transduction in hearing, ca.1900”, Julia Kursell (University of Amsterdam) focused on Carl Stumpf’s discussion of his Siamese recordings published in 1901,[10] where a team at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv showed how documentation relates to cognition in a new way and that the steps and functions of transduction and documentation shift in the order of the chain of hearing. She began by playing Stumpf’s cylinder recording of a Siamese theatre ensemble from 1900 and asked for feedback from the workshop participants who gave a variety of different responses, from identifying instruments, comments on exoticism to the quality of surface noise. Stumpf’s article documents several things: the visit of the ensemble from Bangkok to Berlin; the process of documentation and recording media used and the process of making the recordings, so the process of documenting is here being documented. What interested Stumpf is the way this recorded documentation is listened to, with as many interpretations as there are listeners in the room. Although most will agree on the most important aspects of what they hear on the recordings, to begin with, everyone has a different impression.

The German philosopher and psychologist Carl Stumpf is immensely influential being the founder of several disciplines such as music psychology, comparative musicology, ethnomusicology and experimental phonetics. His early publications “On the Psychological Origins of Mental Representations” (1873) and “Tone Psychology” (1883, 1890)[11] made him famous as an experimenter and he went on to found the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv. Stumpf researched the presence of mental predispositions when we listen and the many sensorial aspects involved. He would ask and analyse which mental “presets” and “attitudes” guide our perception. Such presets may implicitly shape how we perceive sound, music and language. Stumpf developed an “interference apparatus” – a complex system of listening tubes that were distributed through several rooms at the Berlin Institute of Psychology. The apparatus was used to test the responses of groups of listeners, located in different rooms, who listened to vowel sounds being sung in another room. Each group was composed of: persons with or without musical ability; those with or without knowledge about the sound they will hear and musicians from Germany or from Bangkok. In this way, he was able to analyse the groups’ responses according to different conditions or mental presets and also their cultural backgrounds. Through these means, Stumpf attempted to formulate an understanding of how different people respond to or judge music and sound.

His article also gives guidelines for documenting and analytical listening; he advocated using familiar notation in order to transcribe ethnographic music, while indicating differences with additional signs or graphics and used shorthand copiously. With regard to technology, he proposed using electronic, magnetic recording at a time when the prevailing acoustic recording technology was still in its infancy. Attention is paid to the use of recording technology so as not to interfere with or influence the performance. He questioned methods of comparative musicology proposing that the same ethnologist should record and analyse or notate recordings, not two separate minds. He was mindful of the need to develop strategies for archiving and preserving documents and recordings and foresaw mathematical and optical methods of browsing archival material well before microfilm, computers, scanners and AI. What is remarkable is that Stumpf’s strategies for documentation are so well reflected, at a time of transition from one experimental culture which saw experiments performed with living subjects to one where new media technologies began to play a huge role. Stumpf bridged the gap between the two, at the same time reflecting on all the means at his disposal. Regarding the new medium of sound recording with the phonograph and documenting techniques, Stumpf reflects on how they interfere with his own mental preset. When attempting to notate the music of the Bela Coola players from British Columbia in 1886 he observed an impulse to notate what he knows, rather than what is alien to him, that he is unable to move too far from his own mental preset. In using the acoustic sound recording technology of the era, he observes the in the way in which his recording devices distort their sound subjects and performed experiments to investigate how timbre may be affected through manipulation of the phonograph. Stumpf notices that changes in timbre and sound are another separate loop of perception that we innately seek to control.

Tim Boon, Head of Research at the Science Museum, London, delivered his provocation, entitled “Histories of Use in a Science Museum: Potentials & Practicability”, via Skype. He used the term “histories of use” to define a museum-born approach, closely related to media archaeology, that looks at the specific ways in which people in the past handed objects such as tools, machines or instruments to achieve particular results, namely those tacit skills that went unrecorded. The U.K.’s Science Museum Group has ambitions to develop research in this field using objects in their collection, to build an archive of the histories of how these objects were built into the lives of people in the past at work, home and play. Such research would also be used to enhance museum displays. The investigations will involve oral history, simulation-based re-enactment, reconstruction and replication. Tim Boon went on to recount the practical and methodological challenges of establishing a “Histories of Use” programme at the Museum. He cited opportunities that were explored in the recent past through collaborations with sound artist-in-residence Aleks Kolkowski, that made use of objects in the Museum’s collection of early sound recording and reproduction notably in the reconstruction of the giant exponential Denman Horn and reenactments with the Auxetophone-Gramop.

Further attempts in the sonic field however, were not so successful and a project conducted by Christianne Blijleven at the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, U.K. met with difficulties in attempting to do practical work with three electronic musical instruments, namely a 1928 Theremin, a 1970s Mellotron electro-mechanical sampling keyboard and a 1980s Fairlight digital sampler and synthesiser. Reasons why the project failed to deliver a public event with any of the three instruments was due to a combination of factors including the Museum’s own policy with regard to conservation, together with a lack of time and availability of experts and technicians who were needed to participate in open sessions demonstrating the operation and maintenance and of the instruments. The project served to show that to operate museum objects in an ethical and controlled way takes real resources, however, the intellectual and practical reasons for doing histories of use research using museum objects are incontestable.

In response to Boon’s provocation, it was suggested that a better approach might have been to work with collectors of the aforementioned instruments who own functioning examples. While this is a path that the Museum is currently being forced to follow, questions remain about the exalted status given to objects in collections, putting museum objects beyond use (especially if they are not globally unique). If, for example, the Museum’s theremin could be regularly played in public events (as had often been done with museum objects in the past) perhaps at some stage it might become unrepairable although it’s appearance would not necessarily be radically changed, in which case the now non-working object would still be available for visual inspection and could therefore still be exhibited. In contrast to the 1960s and 1970s when all kinds of historical objects were being demonstrated every week, the current situation in the U.K. is that major museums are unable to operate the objects in their collections, bar very few exceptions.

Changes in Museum policy around conservation has had unintended consequences; there was no intention to stop the operation of objects. Because of this, there are devices in collections whose mode of use will become increasingly hard to understand. An argument was made for museums to maintain a reference collection of objects to be kept in their original condition and for them to locate or acquire duplicate objects that could be restored and liberated to do useful interpretive work on behalf of the historical record and on behalf of audiences. Alliances could also be formed with those who use and maintain such objects in the outside world or institutions and universities that have their own collections that may not be subject to the same strict rules around conservation. There is a clear need for collaborative doctoral programs where researchers engage in practical work together with curators and conservators, and the Museum has a long history of reconstruction and replica projects, notably the Charles Babbage Difference Engine No.2 (1991) but such projects are dependent on funding.

In her talk, entitled “Aspiring to Achieve Historical Accuracy in Reconstructions of Artist’s Oil Paint and the role of Documentation”, Leslie Carlye discussed the concept of “Historical Accuracy” and how thorough documentation is essential for the products of the re-enactment to serve as reference materials now and in the future. Her work in the restoration of paintings led to a publication and the database Historically Accurate Reconstructions of Artist’s Oil Painting, which includes recipes for artists’ materials from ca. 1750 -1900. She began by reconstructing these recipes, however, instead of relying on more traditional reconstructions or copying techniques, she employed what she terms as “historically accurate reconstructions”. For example, a recurring theme in 19th century painting manuals was a complaint about the greasiness of dried oil paint and difficulty of applying fresh paint onto its surface. This problem of non-adhering paint can lead to an effect known as “crawling”. Carlyle’s reconstruction of the paint that reproduced those greasy layers, was made following her concept of historical accuracy; through the use of traditional methods of clarifying and preparing the oil for use in the paint and hand-making the paint using the reconstructed materials.

In formulating her terminology, Carlyle used the ISO definition where accuracy equals the closeness of a measurement to the true value using the analogy of a circular target where the bullseye represents true value and the the closer the ‘hits’ or black dots are to the bullseye, the more accurate they are.[12] Of the various configurations of accuracy and precision, the target that shows high accuracy with low precision best suited her purpose; if the bulls-eye is historical accuracy, then as it is impossible to reproduce the past, efforts to reach this ‘true value’ can only be aspirational. If one applies this to the study of past practises by artists, what is important is the relative position to the bullseye, or closeness to our impossible goal. The visual analogy demonstrates that using modern artists’ paint doesn’t go anywhere near the bullseye, whereas using traditional oil and pigment-based paint starts to get us somewhere in the circle.

Documentation was important at all stages, before, during and after making reconstructions. In order to begin to reconstruct the oil paint described above, Carlyle researched hand-written documents in the 19th century archive of colour manufacturer Windsor & Newton, between 1834 -1858, as there were numerous production methods or making oil paint using multiple ingredients, a system was devised for identifying patterns in the use of materials. This showed that Windsor & Newton standardised their formulation between 1850-1858, the researcher sought a recipe that was representative and constantly used, not one picked out at random. A comparison of contemporary artists’ manuals with Windsor & Newton’s archive showed that some ingredients were used for longer periods than others. One case study examined the hitherto unexplainable 19th century phenomenon of “paint-breakdown”, occurring ten years after a painting was completed. The only recourse was to reconstruct and analyse the paint. During the reconstruction, documentation took on a new role; noting properties and behaviour of the different ingredients; compiling a vocabulary to describe differences in the feel and behaviour of the paint, using terminology e.g. with different oils, one being more “buttery” another “stringy” with less resistance or cohesion felt during brushing; noting how paint would behave differently according to the substrate it was applied to and in order to monitor the behaviour of the paint over time and for use as samples for study.

Documentation meant keeping track of precisely what was in each reconstructed paint e.g. through labelling. Documentation during and after was essential for the meaning and usefulness of these samples and involved many pages of coded sample descriptions. A code was used to find what day it was made, the ingredients and percentage of materials and where they came from, what the conditions were and what substrates were used. The documentation part of the project was totally underestimated in terms of time & funding and had to be written up after the fact. However, all members of the team were rigorous in making lab notes, their training in conservation made them preconditioned to taking close notes on what they were doing, how they were thinking about what they were doing and why they were doing it. This information and images of the work process was stored on disc and became a primary source of information. The reconstructions showed that certain effects in paint were not artist applied but occurred on their own as a result of chemical reaction over time. The reference samples produced by the project help us understand what happens to paint as it ages and these physical samples become more valuable with time as they age – they undergo the same slow chemistry as in paintings. However there are issues of storage. Carlyle had to develop new forms of storage in order to protect the oil paint samples.

The term “historical accuracy” was criticised at the time by colleagues in conservation who took it literally to mean recreating the past, not understanding that accuracy is relative, it is aspirational and can rightly be applied to methods that go as far as possible in recreating historical paint and glue making. With regard to precision versus accuracy, it was asked if the original actors related to such a distinction when making their craft, in terms of what they were trying to achieve. In answer, they would have sought the most appropriate materials for their needs, those that would work well and that were durable. In the production of paint, precision is important in maintaining quality. However, there were economical concerns too in terms of costing and issues of scale as industrial methods involved massive amounts of ingredients. The concept the original arose, it was thought not make sense in this case as there are so many variables. Randomness has to be allowed for as materials may change according to availability and in their composition. There is an assumption that 19th century painters of the so-called “golden age” had perfected oil painting, that their knowledge and understanding of it has been lost, but they themselves were continually experimenting and in search of perfect methods.

In a change to his planned provocation, Benoît Turquety showed examples of projects he had been involved with in terms of experimentation with and documentation of historical film technology. While suggesting that experimentation with machines has not been done to any great extent in the discipline of film studies, he gave two contexts in which experimentation has taken place. The first, a research project on Bolex cameras (“Bolex, Film Technology and Amateur Cinema in Switzerland” 2018), was not done with the collection of the Cinémathèque suisse itself but with collectors who were willing to share their expert knowledge. The project has compiled a history and information on Bolex cameras and plans to include further content from participating students about the cameras, collections and practices of use. In one case, a PhD student focused on the interaction between the machine and its users, examining cameras by weight, sound, design features and gestures when handling them. Another aspect of hands-on work dealt with the engineering history of the cameras; the student worked together with a Paillard-Bolex engineer, taking apart different models in order to compare them, examining components, design and even the noise of the machines in operation. The idea was to see what can be learnt from opening up cameras and examining their mechanisms and component parts. While this may or may not concern the user who might be more interested in the surface of the machine and its interface, nevertheless, the internal workings of the camera should be investigated.

The second example concerned the TECHNÈS project, an international Research Partnership on Cinema Technology that connects the Universities of Lausanne, Montreal, Rennes, the cinémathèques of Quebec, France, Switzerland, among others. This enormous project is currently developing an online encyclopaedia of film technology, hosts interviews with filmmakers and technicians, and organizes conferences and demonstrations by specialists. Its demonstration videos are “clean”: their aim is pedagogic and mainly for lay film students. TECHNÈS has invested heavily in creating 3D scans of objects which the viewer is able to inspect and zoom into the object from every angle. These are time-consuming and expensive to make. Turquety questioned their value and what they can tell us about an object aside from surface information. Technical objects are worthless if not connected with an infrastructure and users. The 3D representation of the scanned objects gives no information as to weight, size, feel, operation or sound. A TECHNÈS conference in Montreal, 2019, invited researchers to propose conference papers based on objects in the François Lemai collection. Those selected were given a day to work with the physical object together with a technician, in order to closely examine and manipulate the objects they were to present on, then have another day to re-think their paper and present at the conference in the usual fashion. Unfortunately, the work with the collection – the laboratory part – was not documented, only the conference presentations.

Turquety then showed two video recordings of demonstrations with historic screening technology. The first video demonstration featured a projection of lantern slides, conducted by two specialists: a curator-historian and an technically proficient collector. The aim was to produce a “clean” demonstration of the technology in action. However, the video showed them confronted by technical problems, being unable to successfully project an image despite repeated attempts and failing to get the result they expected. This is interesting in terms of documentation as it shows the limits of expert knowledge when faced with little-understood technical problems and an other than imagined outcome. The second video, featuring a rare type of kinetoscope, presented another set of problems in terms of documentation. What was documented first is a love of the object itself, an appreciation of its aesthetic qualities, the beauty of its mechanism and the fragility of some materials. This appreciation is arguably crucial in a pedagogical context as people wish to have a tactile (and visual) experience of the object. The method of projection is explained in the demonstration, but at some point the lantern had to be adjusted, which was not easy. At this moment, the demonstration moved away from abstract knowledge of the object to real-life technical knowledge. The specialist giving the demonstration comments that the apparatus is working wonderfully, however, the footage gives the exact opposite impression. How should we judge this documentation and its claims? To what extent does the judgement of the specialist take into account the age and condition of the object? Must one judge what one sees through the camera lens, or on what the specialist is seeing?

The video documentation is edited, however it does preserve some hesitations and mistakes. What is missing are the movements and gestures of the projectionist who turns the crank; we only see what is projected on the screen. It would have been valuable to document the operation and regulation of the machine and the gestures performed in doing so. These views may have been filmed but perhaps they didn’t make the final edit. However, such rushes or raw footage could potentially be of use to researchers. Including mistakes and failures in the documentation is laudable, but also problematic as we are only given a limited amount of information. Some aspects, Turquety argued, may be lost in the final documentation that are nonetheless crucial to the experience.

A discussion followed on video documentation. In fairness to the specialist mentioned above praising what appeared to be distorted images, when filming a projection on a screen, the camera may record differently to what the eye sees, often producing what is known as the “shutter effect”. A series of videos by Paolo Brenni, historian of science at the Fondazione Scienza e Tecnica Florence, was recommended as a highly valuable resource. Brenni reenacts a number of historical scientific experiments using original historic instruments from the museum. The videos are presented without commentary and the experimental process and the handling of objects are very clearly shown. The issue of filming a lanternist at work was raised as much of this work is done in near darkness. It is therefore questionable if documentation of these activities using lighting makes any sense at all as it is not an authentic experience. It was suggested that this produces a misunderstanding of how the object is handled.

Final discussion on documentation

The issue of documentation interfering with an experiment is a recurrent problem that occurs in scientific laboratories too; there is a patent contradiction in the dispositif of the experiment. Documentation presents numerous problems and should be based on the idea of a compromise. The experiment is done in a laboratory context – not a performative one – and the experiment should be recreated for the camera. It is interesting to think not only of the experiment that is being documented, but also on the way the documentation is made as an imaginary of technological reenactment. We should analyze the documentation as a representation of how we think a media archaeological experiment should be performed. The way in which the documentation is edited, the way the handling and operation of objects is shown, should be analysed as a framed and edited representation of an experiment. It is an ideological representation of what took place in front of the camera. Since these problems are largely inescapable – even when using 360 degree cameras and continuous filming – one may wonder if the documentation should be edited with a certain type of viewer in mind? Other projects have struggled with similar problems. Editing may be thought of as a form of presentation of one’s evidence. Ideally, three different versions should be produced for different purposes and types of audience: a short 90 second clip that could be used in a lecture, a longer one of mid-length for use in a seminar or online, and a full-length source that is made available for researchers.

In the selection of material and how to highlight what is important, a case was made for using documenting tools and techniques other than video cameras. Medical drawings, for instance, were not made obsolete by the medium of photography, because they select and guide or prioritise what the viewer looks at. Video material can be “flat” and unselective, giving a lot of information, while at the same time making it difficult to focus on what may be important. Serious thought needs to go into the editing of documentation about the story one wants to tell. With 3D scans, they give an illusion that all the information is there, but what do they actually tell you about the object? Objects belong to a wider performative context, in which the object is being handled. While 3D scans are very much like museum objects in a glass case, they can provide some interactivity in certain contexts. In that sense, one should think about documentation in terms of transmedia storytelling: using the most appropriate media means to explain or show the work.

Regarding the archiving of the copious documentation generated in projects such as ADAPT or Carlyle’s database of historic artists’ paint, there is a sense that we are preserving it for a future we don’t know. The dichotomy discussed in Boon’s talk between curators and conservators raised questions about the use of museum collections. The purpose of a collection is that it should be preserved and made available for future generations. Objects may have value, only insofar as they actually work, but on the other hand there is another kind of value in them not working. More dialogue is needed. Conservators wish to facilitate research and not hold back knowledge, but at same time need to prevent wear, damage or to use something up that is unique. Some objects were mass-produced though, so there is a scale of uniqueness to consider and examples should be acquired for experimentation. In closing, it was posited that artefact-based research and research based on trying to preserve know-how (as in ADAPT) require very different approaches. With objects, all uses are possible. They may be given to artists to re-purpose for all manner of functions that were never foreseen, for instance. However, researching the knowledge and craft that are inscribed in the history of uses of the object require distinct methodologies and forms of documentation.

Notes

[2] Erkki Huhtamo, “Thinkering with Media: On The Art of Paul DeMarinis,” in Paul DeMarinis: Buried in Noise, ed. Ingrid Beirer, Sabine Himmelsbach, and Carsten Seiffairth (Heidelberg and Berlin: Kehrer Verlag, 2010), 33–46.

[3] Andreas Fickers and Annie van den Oever, “Experimental Media Archaeology: A Plea for New Directions,” in Technē /Technology: Researching Cinema and Media Technologies, Their Development, Use, and Impact (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2014), 272–78; Andreas Fickers and Annie van den Oever, “Doing Experimental Media Archaeology: Epistemological and Methodological Reflections on Experiments with Historical Objects of Media Technologies,” in New Media Archaeologies, ed. Ben Roberts and Mark Goodall (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 45–68; Andreas Fickers and Annie van den Oever, “(De)Habituation Histories: How to Re-Sensitize Media Historians,” in Hands on Media History: A New Methodology in the Humanities and Social Sciences, ed. Nick Hall and John Ellis (London: Routledge, 2019), 58–75; Andreas Fickers, “How to Grasp Historical Media Dispositifs in Practice?,” in Materializing Memories: Dispositifs, Generations, Amateurs, ed. Susan Aasman, Andreas Fickers, and Joseph Wachelder (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 85–99; Annie van den Oever, “Experimental Media Archaeology in the Media Archaeology Lab: Re-Sensitizing the Observer,” in At the Borders of (Film) History: Temporality, Archaeology, Theories, ed. Alberto Bertrame, Guiseppe Fidotta, and Andrea Mariani, 2015, 43–53.

[4] See, for instance: Aust, Rowan & Murphy, Amanda & Jackson, Vanessa & Ellis, John. (2015). “Adapt Simulation: 16mm Film Editing for Television,” VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture 4, no. 10 (2015), DOI: 18146/2213-0969.2015.jethc077, and Nick Hall and John Ellis, eds., Hands on Media History: A New Methodology in the Humanities and Social Sciences (London: Routledge, 2019).

[5] Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Experimental Systems: Historiality, Narration, and Deconstruction (Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1994).

[6] Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997).

[7] For more information, see also the blog post “An Experimental Media Archaeological Approach to Early-Twentieth Century Home Cinema” on the C2DH website: https://www.c2dh.uni.lu/thinkering/experimental-media-archaeological-approach-early-twentieth-century-home-cinema.

[8] Cf. Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, An Epistemology of the Concrete: Twentieth-Century Histories of Life, Experimental Futures : Technological Lives, Scientific Arts, Anthropological Voices (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

[9] Erkki Huhtamo, “The Dream of Personal Interactive Media: A Media Archaeology of the Spirograph, a Failed Moving Picture Revolution,” Early Popular Visual Culture 11, no. 4 (November 2013): 365–408, https://doi.org/10.1080/17460654.2013.840247.

[10] Carl Stumpf, “Tonsystem und Musik der Siamesen”, Beiträge zur Akustik und Musikwissen-schaft 3 (1901), 69-138.

[11] Carl Stumpf, Uber den psychologischen Ursprung der Raumvorstellung (1873) & Tonpsychologie, 2 voll. (1883, 1890).

[12] https://manoa.hawaii.edu/exploringourfluidearth/physical/world-ocean/map-distortion/practices-science-precision-vs-accuracy